Known as the Football Card King, Baines began the trends that included swap systems and desperate hunts for elusive players

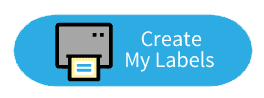

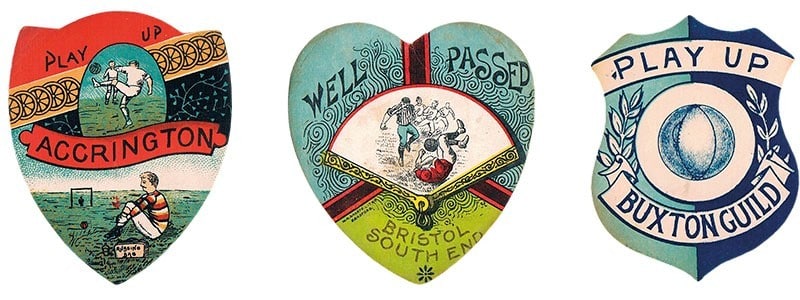

15 October ~ In 1887, John Baines, a toy retailer from Bradford, filed a patent describing “a new means or method of illustrating the play and players of football”, later categorised as “football cards”. Baseball cards had been popular in the US since the 1860s, and Baines thought football cards could be just as popular in Britain. His colourful cards were cut into the shape of a shield and featured depictions of teams and kits, with sketches of popular players. They were sold in packets of six for a halfpenny (worth around 20p today). Baines went on to produce rugby and cricket cards, and eventually covered scores of different sports, from golf and tennis to horse racing and bowls. But it was the football cards that made his fortune, and saw him adopt the title of “The Football Card King”.

Baines produced hundreds of thousands of football cards each year, operating from his “Dolls’ Hospital” toy sales and repair shop on Bradford’s North Parade. Something of an eccentric, he distributed his cards from a distinctive carriage pulled by a horse with a monkey on its back. As well as covering professional clubs, Baines produced cards for hundreds of amateur and local clubs. A rummage through modern collections reveals cards for long-defunct sides such as Imperial Rovers, Rotherham Swifts and Heckmondwike Casuals, plus cards for the likes of Newton Heath and Newcastle East End, the clubs that respectively became Manchester United and Newcastle United.

The cards were promoted via various ingenious prize competitions, which could be won by finding certain “medal cards”, by collecting piles of empty packets, or by submitting mini essays, with winning efforts printed on the back of subsequent cards. Most prominently, Baines offered football jerseys to whoever could collect a specific list of cards, set out on posters in shop windows. Some of the listed cards were particularly hard to find. “Boys would tramp miles to districts where, according to rumour, the rare and fabulous ‘listers’ were in every packet,” recalled one collector, writing as “Northerner” in the 1950s. “They never were, of course.”

“I remember one boy who managed to collect a full set,” said Northerner. “He came to school one morning wearing a magnificent sweater. We all crowded round him to admire it. But I found out afterwards that his father kept a newsagents shop. The thought that he might have taken the winning cards out of the packets before we could buy them still rankles.”

Other young collectors sought work at the Bradford printing firms where the cards were printed and packed. These apprentices were paid very little, but they enjoyed the considerable perk of being able to leaf through reams of cards during their lunch breaks in search of “listers”. “There must have been many printers’ apprentices in Bradford wearing ill-gotten new football jerseys,” said Northerner.

The gaming aspect of football cards created controversy in 1888, when Bradford grocer Steve Binns was summoned to court for selling “certain prize packets, they being lotteries not authorised by Acts of Parliament”. A complainant, who had purchased four halfpenny packets of Baines cards from Binns, argued that the cards were lottery coupons, which were illegal. Magistrates decided there was “not the ghost of a case”, and dismissed it.

Swapping was, of course, an essential part of collecting Baines cards, but rather than “got, got, need” bartering, cards were exchanged via games of skill. The most popular game was “skaging” or “who’s nearest?”, in which players would take turns to flick their cards against a wall, in a winner-takes-all contest. Repeated “skaging” caused damage to the flimsy cards, which is one of the reasons why good condition examples are very scarce today.

As the popularity of Baines’ cards grew, competitors arrived. The most notable was WN Sharpe, also based in Bradford, who produced “Play Up!” cards, named after the then-popular terrace exhortation. Tobacco and soap companies also began to issue football cards, but Baines warned his customers: “Do not be gulled by feeble imitations.” He remained, he insisted until the sale of his company in the 1920s, “the sole inventor and originator of the famous packet of football cards”.